·

·

·

Market shaping involves using the power of markets to address challenges where commercial incentives for innovation fall short of their social value – think neglected diseases, vaccines for future pandemics, green cement, sustainable aviation fuel, etc. Market shaping seeks to accelerate innovation by rewarding innovators for solving pressing global challenges.

Below, you will find an assortment of writings, introductory explainers, and a glossary, all designed to offer a broad overview as well as a deep dive into the world of market shaping economics.

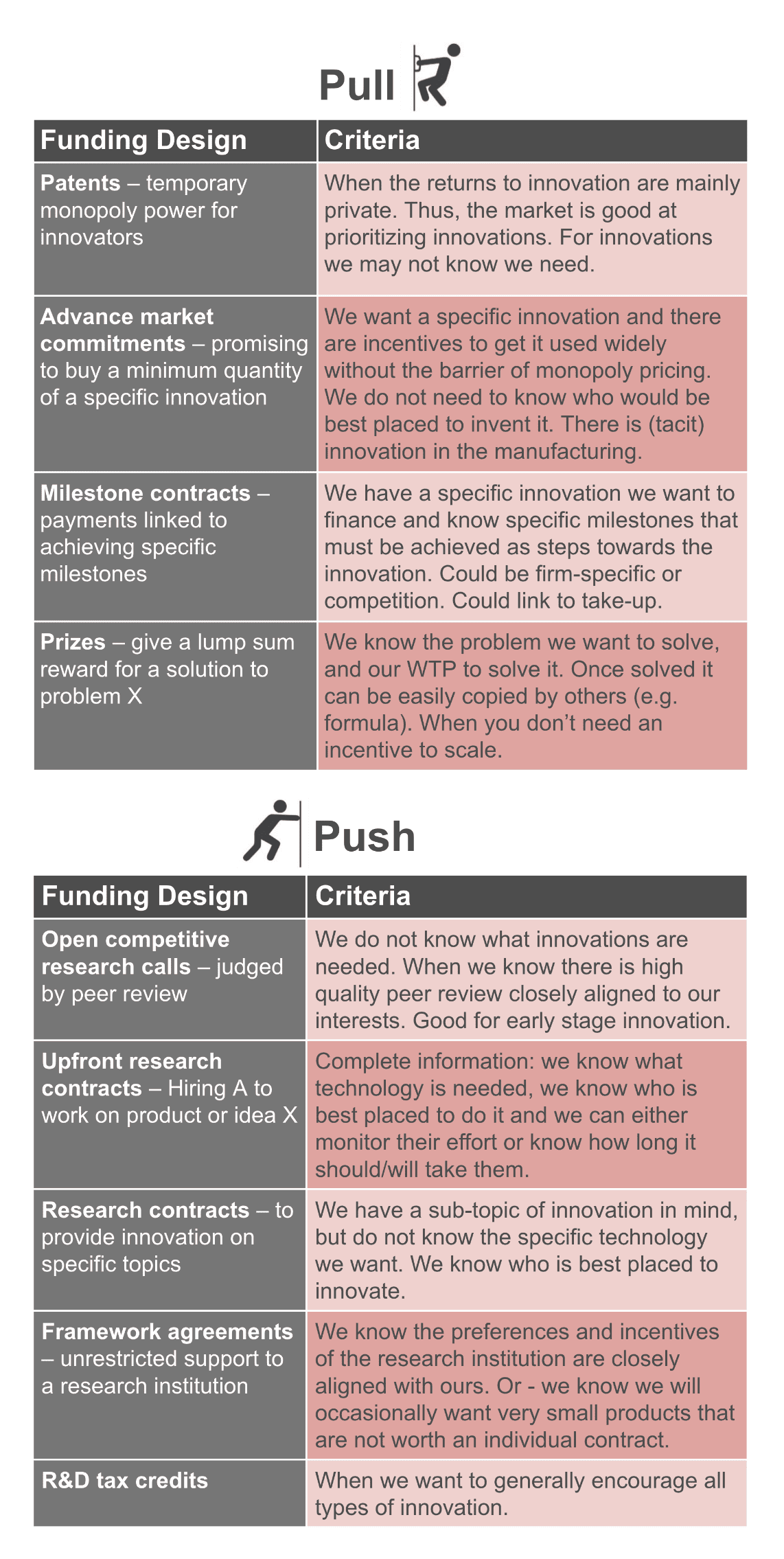

Pull mechanisms are policy tools that create incentives for private sector entities to invest in research and development (R&D) and bring solutions to market. Whereas “push” funding pays for inputs (e.g. research grants), “pull” funding pays for outputs and outcomes (i.e. prizes and milestone contracts). These mechanisms “pull” innovation by creating a demand for a specific product or service, which drives private sector investment and efforts towards developing and delivering that product or technological solution.

One example of a pull mechanism is an Advance Market Commitment (AMC), which is a type of contract where a buyer, such as a government or philanthropic organization, commits to purchasing (or subsidizing) a product or service at a certain price and quantity once it becomes available. This commitment creates a market for the product or service, providing a financial incentive for innovators to invest in R&D and develop solutions to meet that demand.

An AMC was used in the early 2000s in the case of developing a pneumococcal vaccine for the strain of the virus affecting children in low and middle income countries. Another current example is Frontier, led by Stripe, which is an AMC to accelerate carbon removal.

In general, pull mechanisms are useful when we know we need an innovation, but we don’t know who is best placed to develop it or how.

The Economics of Market Shaping with Susan Athey, Michael Kremer, Jean Tirole, and Christopher Snyder

Market Shaping to Combat Global Challenges with Catherine Bremner, Jane Flegal, Matthew Hepburn, and Rachel Glennerster from the MSA launch event at the International Monetary Fund on May 4th 2023.

Market shaping uses economic tools to solve market failures where commercial incentives for innovation trail behind societal needs. One example is advance market commitments (AMCs), which are “pull mechanisms” that tie payments to outputs. AMCs establish legally binding contracts to subsidize the purchase of a large quantity of a specific innovation if it is invented. Other examples include prizes, which are competitions that reward solutions for a specific problem, and milestone contracts, which are payments linked to achieving interim steps toward an innovation.

Commercial incentives for innovations to tackle climate change and prepare for pandemics, under existing market institutions, fall far short of the social value of such innovations. There are several possible reasons for this.

Externalities. Externalities are spillover effects (e.g. pollution) that may not be reflected in market prices. In some cases, innovations create benefits not just or even not primarily for the buyer of the good. A good example of this would be innovations that reduce greenhouse gas emissions, for example in cement production. Existing incentives to invest in these technologies are inadequate because many consumers are unwilling to fully pay for carbon benefits.

Low barriers to entry. There are many cases in which innovations are not patentable, are not easy to protect with first-mover advantages and it is very easy for subsequent competitors to enter the business as well. This reduces commercial returns to develop such innovations.

Idea spillovers are a related idea. Firms may not invest in innovation if they can easily spread to rivals (rivals may be able to reverse-engineer a product). Developing an innovation first and demonstrating it is possible may be costly and firms may only capture a small share of the returns.

Constraints on pricing. Social and political limits on pricing in the midst of pandemics can hold the commercial value of innovations far below their social value. This is not to say such limits are not warranted, but they create a gap between social and commercial value.

Large buyers with bargaining power. In some markets there are only a few buyers, perhaps only the government. In these markets, buyers have a large amount of bargaining power. Once the innovation is developed, these buyers can hold down prices. Firms can anticipate this and therefore underinvest in innovation to begin with.

Firms with (monopoly) pricing power. Some markets are not competitive – there may only be a small number of firms. Patents also provide innovators with temporary monopolies. As a result, these firms may be able to set higher prices. These high prices may exclude people who would benefit from the innovation and value it more than unit cost of production. From an economist’s perspective this involves static social inefficiency (“deadweight loss”).

Poor consumers in low and middle income countries may be unable to afford to pay the higher prices that would make investing in innovation attractive. This will result in underinvestment in innovations needed in those markets.

Behavioral biases. People may undervalue innovations that benefit them in the future or only benefit them with some probability. This may be the case with innovations to address future climate change or pandemic risks. Therefore there will be insufficient demand for them which will reduce the return to innovation.

High fixed costs. Some innovations may have high fixed costs (e.g., research and development, manufacturing capacity) which may deter firms from developing them. Firms may not be able to set prices that enable them to cover their fixed costs. In addition, higher prices may exclude users who value the innovation above the unit cost, which is inefficient (see above on higher prices).

An Advance Market Commitment (AMC) is a type of pull mechanism. It involves making a binding promise, in advance, to purchase or subsidize the purchase of a new product if it is invented. It may involve the firm committing to price at close to unit cost in return for the sponsor (government or philanthropist) subsidizing a large quantity of purchases.

The $1.5 billion Advance Market Commitment for the Pneumococcal Vaccine was launched in 2009 and led to the three vaccines tackling strains of pneumococcus prevalent in low and middle income countries.

Since then three vaccines for the strains of pneumococcus common in low- and middle-income countries have been developed, hundreds of millions of doses delivered, and an estimated 700,000 lives saved. The rate of vaccine coverage for the pneumococcal vaccine in GAVI countries converged to the global rate five years faster than for the rotavirus vaccine which GAVI supported without an AMC.

Think about the minimum incentive that might be required to incentivize a firm to invest in innovation in problems neglected by commercial investment.

The pull mechanism may need to cover the cost of research and development and production capacity.

It might be worth thinking about how this opportunity compares to other investment opportunities for firms in that sector.

For example, this report making the case for vaccine AMCs estimated “$3.1 billion is comparable to the value of lifetime sales of an average pharmaceutical product.” This helped inform estimates of how large a vaccine AMC should be.

It may also be worth thinking about the size of the relevant market. Large global commodity markets may need larger incentives to incentivize firms.

Then think about the value of the benefits of the innovation to society as a whole. That should provide a ceiling on how large a pull incentive should be.

Watch our faculty directors as they introduce the key market shaping concepts

You can find it on the new Market Shaping Accelerator site.